TREATMENT OF CHRONIC DIARRHEA WITH CHINESE HERBS AND ORIENTAL DIET THERAPY

BACKGROUNDDiarrhea refers to a condition of frequent bowel movements, involving mushy, loose, or watery stool. The disorder can be subdivided into broad categories of acute diarrhea and chronic diarrhea. Acute cases can be induced by eating foods that cause a gastro-intestinal reaction resulting in about one day of diarrhea; alternatively, it can occur as a result of the activity of pathogenic organisms contaminating food and/or beverages, which may cause symptoms lasting anywhere from a day (with certain bacteria) to ten days (with other bacteria or viruses). With protozoal and other organisms that remain in the intestines, a persisting, cyclically recurring problem may last for many weeks. The infections and parasites may die off spontaneously, or may survive without causing continued symptoms, but the persisting cases of diarrhea usually require, and often respond to, therapies that inhibit or destroy the offending organisms. Acute intestinal disorders may also occur secondary to certain non-intestinal diseases, including flare-up of chronic liver or gallbladder disease.

Chronic diarrhea may be initiated by an acute disorder that, by some means, becomes self-reinforcing so that it does not clear up over time. Lasting for months or years, modern medical tests may show no obvious infections of the intestinal tract nor imperfections in the structure of the intestinal lining; by contrast, when part of the bowel is surgically removed or has been damaged by a disease, chronic diarrhea can be attributed to those specific causes. The condition of recurrent diarrhea is becoming more common as a consequence of the high rates of diabetes; the elevated blood sugar can trigger the reaction. There is elevated risk of developing hemorrhoids with frequent bowel movements, so this can be a secondary manifestation of the intestinal disorder.

Drugs that reduce intestinal motility may provide temporary relief, but the bowel problem usually returns when the drugs are discontinued (and, sometimes, continues to occur even with regular use of the drugs). In some cases, chronic diarrhea is accompanied by fecal incontinence, which is a different disorder: the anal muscles are unable to retain closure. When the two disorders combine, as occurs with some chronic diseases and with the deterioration of aging, the result is very distressing and debilitating for the person who suffers from it. Chronic diarrhea, because of its weakening effects, may eventually lead to incontinence.

Chronic diarrhea is differentiated from other diseases that may include bouts of diarrhea, such as irritable bowel syndrome (often characterized by constipation interrupted by temporary diarrhea induced by dietary, emotional, or other factors) and ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease (in which there is a marked pathology of the intestinal wall associated with autoimmune processes, and worsened by nervous system hyperactivity). These disorders are discussed elsewhere (see: Irritable bowel syndrome; Jian Pi Ling and treatment of ulcerative colitis).

Two abnormal processes are of primary concern:

- Insufficient absorption of water from the colon, and, sometimes, insufficient breakdown and absorption of other food substances, such as fats and complex carbohydrates from the small intestine;

- Excessive intestinal peristalsis, which moves the fecal material through the intestines more rapidly than usual, reducing time for absorption of fluids and nutrients and passing the material to the rectum in a relatively short time (a few hours).

Chinese medicines may beneficially impact both these processes.

ORIENTAL VIEWNormally, the purified qi derived from food and drink is transported upward by the spleen to the lung, while the left-over food matter is passed to the intestines for further separation and eventual elimination of the waste materials. The fundamental cause of persisting diarrhea, according to the ancient Chinese medical texts, is the descent of clear splenic qi. If significant additional dampness is also retained with the descending clear qi, then the condition will be more severe.

Why does the spleen qi descend rather than ascend? There are three traditionally recognized causes. According to Jingyue Chuan Shu (A Complete Collection of Jingyue’s Works, 1624 A.D.): “Diarrhea is the result of an improper diet, seasonal pathogenic factors, and retained cold [that occurs] after eating raw or cold food (1).” These may be explained as follows:

- Improper diet (see the section on Oriental diet therapy below), including overeating, not chewing food adequately, irregular meal schedules, or eating the wrong types of foods according to constitutional and disease status indications, disturbs the function of the spleen and then also burdens the intestines with foods that are difficult to separate. It is a case of overwhelming the normal functions of the spleen;

- Cold foods impair the spleen by overly chilling it (warmth aids the rise of qi, coldness its descent) and raw foods may contain large amounts of indigestible fiber and, more importantly, live pathogens, all of which can contribute to rapid intestinal transit. The “cold spleen” is functionally restricted;

- Seasonal pathogenic factors, especially dampness and the heat/damp combination that was often experienced in the summer (see The six qi and six yin), overwhelm the spleen’s natural function of separating and dispersing moisture; summer heat syndrome refers primarily to the result of consuming contaminated foods and drinks rather than to the time of year or the temperate conditions, which is when the contamination most often occurred.

With these possible initiating causes of diarrhea, the persisting case is seen to arise primarily because of spleen yang and kidney yang deficiency syndromes. The spleen yang is unable to distribute the qi upward, so the qi descends with the turbid food residues. The kidney yang is unable to warm and invigorate the spleen, so recovery of normal function of the spleen and regularity of the bowel conditions cannot easily occur. The pathogenic organisms are not eliminated because the qi—lacking the vigor of spleen and kidney yang—can not fight them. Diarrhea experienced over an extended period of time further weakens the yang, because of its repeated downward draining of qi, thus perpetuating the symptom.

Yang deficiency is often experienced by the elderly and by those who have suffered chronic diarrhea for a very long time, but can occur at any age. In a clinical report on chronic diarrhea in children (2), the role of spleen yang deficiency in those cases is emphasized:

Chronic protracted diarrhea in children is mainly caused by improper feeding, infantile dyspepsia, insufficiency in physical constitution, debility, as well as improper treatment of acute diarrhea. Exhaustion of qi and injury to yang often follow long-lasting diarrhea, and hence the theory “persistent diarrhea will injure the spleen yang.” When the spleen yang is impaired, water and food will be unable to be digested, metabolized, transformed, and transported. These will, in turn, induce accumulation of water and turbidity, and disorder in the ascending and descending functions. As a result, diarrhea becomes protracted and difficult to cure. The crux of the disease is the insufficiency of the spleen yang, therefore, the key point in the treatment of the disease is to warm up and invigorate the spleen yang and restore the normal function of transformation and transportation of the spleen.

In a report on the spleen/stomach system of Chinese medicine and how it affects intestinal functions (3), it was noted that:

Lack of, or poor, ascending circulation [of the spleen qi] is due to irregular meals and improper food intake, emotional trauma and mental or physical exhaustion. Any of these factors damages the spleen yang qi, resulting in dysfunction of splenic circulation and transformation, and weak ascending power. Accompanying signs are manifested in chronic gastritis, chronic enteritis, dysfunction of the stomach and intestines, chronic hepatic or biliary tract diseases, malnutrition, and general degeneration and weakness or ptosis of internal organs. The inability of the spleen to perform healthy circulation is due to poor ascension of the spleen yang qi and may be manifested as deficiency and weakness of spleen qi, as dormant spleen yang, or as sinking of the central qi....The kidney yang is also known as the fire of life gate [mingmen]. It has a propulsive action in the digestive function of the spleen and stomach. If there is an insufficiency of the life gate fire, the digestive function of the spleen and stomach is reduced, with accompanying signs of spleen and kidney yang deficiency complex, such as edema, cold abdominal pain, prolonged diarrhea, early morning diarrhea, or stool with undigested food particles may occur.

In the widely used text Formulas and Strategies (4), there is described an “abandoned disorder” from the loss of fluids that occurs through chronic diarrhea, which involves a cycle of debilitating effects:

In such cases, the spleen qi has become deficient and the intestines have lost their stability and capacity to absorb. This results in unremitting diarrhea to the point of incontinence....Long term diarrhea not only leads to deficiency of the spleen qi and yang, but also invariably involves the kidneys. This aggravates the diarrhea, which further injures the spleen and kidneys, which in turns worsens the diarrhea, and so on in a vicious circle.

Even when initiated by a pathogenic organism, this debilitating cycle could only be partially rectified by removing the offending organism through drug therapy: the spleen and kidney would still be severely weakened. When drug therapies aimed at eliminating parasites and other organisms that cause diarrhea are ineffective, it may be that any microorganisms that participated in the early stages of diarrheal disease are now gone, but the weakness persists. The description in Formulas and Strategies continues:

When the spleen and kidneys are deficient and cold, there is fatigue and lethargy as well as mild, persistent abdominal pain that responds favorably to local pressure or warmth. When the spleen is weak, the appetite declines, food intake is reduced, and the complexion becomes wan. Kidney yang deficiency is further expressed in the sore lower back and lack of strength in the legs. The pale tongue with a white coating, and the slow, thin pulse are indicative of deficiency yang of the spleen and kidneys.

In another section of the book, it is also stated that “Chronic diarrhea depletes the fluids, which exhausts the yin and blood.” Thus, an overwhelming debility of yin, blood, and yang may eventually arise.

Chinese Herbal Treatments

The fundamental principles of treatment involve warming the spleen and kidney yang, dispersing the excessive dampness, and astringing the discharge (stabilizing the intestines). An example of a formula recommended for chronic diarrhea is Zhenren Yangzang Tang. The formula consists of ginseng (or codonopsis), atractylodes, cinnamon bark, nutmeg, terminalia, papaver, peony, tang-kuei, saussurea, and licorice. For patients with extreme cold condition, aconite and dry ginger are added to the herb formula. Since papaver (poppy capsule) is not available for use in the West, the patient would take a drug substitute, such as opium tincture or loperamide. When taking the formula, in order to obtain desired results, one should not consume “alcohol, wheat, cold or raw foods, fish, and greasy foods.” These restrictions illustrate the importance of linking diet therapy with herbal therapy.

In presenting the famous herb formula Sishen Wan (Psoralea and Nutmeg Formula), there is this preliminary discussion of diarrhea associated with spleen and kidney deficiency in Formulas and Strategies:

When the yang of the spleen and kidneys is deficient, there is a lack of interest in food; and because the deficient spleen yang is unable to cook or decompose the food, what is eaten is not digested....When the yang is deficient, the spirit cannot become fully animated. This lack of animation is manifested as fatigue, lethargy, and a dispirited demeanor.

The formula is comprised of psoralea, evodia, nutmeg, and schizandra; the first two ingredients being quite warming, and the latter two being astringents. The pills made from these herbs, ground to powder, are prepared with dry ginger and jujube. Aconite and cinnamon bark can be added when the diarrhea and cold conditions are extreme: “When the spleen and kidneys are warmed and the large intestine is stabilized, the transformation and transportation of foodstuffs will resume, and the diarrhea will cease.” An alternative formulation relies on psoralea and nutmeg combined with fennel and saussurea. Saussurea is used in some of the diarrhea formulas “because of its specific ability to alleviate tenesmus [intestinal cramping]. It also prevents the astringent, binding properties of the other herbs from causing stagnation.”

Shen Ling Baizhu San (Ginseng and Atractylodes Formula), a well-known formula for spleen qi deficiency and diarrhea, is described in Formulas and Strategies as indicated for “loose stools or diarrhea, reduced appetite, weakness of the extremities, weight loss, distention and a stifling sensation in the chest and epigastrum, pallid and wan complexion.” The formula contains ginseng, atractylodes, hoelen, licorice, coix, dolichos, dioscorea, lotus seed, platycodon, and cardamom. Using modern research methods, it was shown that a formula similar to Ginseng and Atractylodes Formula, called Qinggong Baxian Gao (Qing Court Eight Immortals Paste), promotes the absorption of fats and complex sugars, compounds that, when malabsorbed, contribute to diarrhea. In laboratory animal experiments, this herb formula helped heal intestinal ulceration and restored vigorous growth of the duodenal mucosa with just two weeks daily treatment. Among its ingredients are ginseng, hoelen, lotus seed, coix, and dioscorea.

Zhao Lichen and Chen Fang (5), in an article on food therapy for diarrhea, mention the following general treatment principles:

- use fragrant herbs to dissolve the turbidity [especially for summer-heat type disorder]

- clear heat and promote the removal of wetness [especially for damp-heat type of disorder]

- support the spleen and restrict the liver [especially for liver qi stagnation affecting the spleen]

- warm the kidney and strengthen the spleen [especially for chronic diarrhea]

- use astringent measures for consolidating the intestines and arresting diarrhea [for all types of diarrhea]

They have recommended some sample food therapies, mentioned below, but these principles can be utilized to formulate an herbal prescription. For example, the following combination (to be made as a decoction or granule mixture) is a means to possibly halt the persisting diarrhea:

| Codonopsis (dangshen) | 14% |

| Atractylodes (baizhu) | 10% |

| Coix (yiyiren) | 10% |

| Lotus seed (lianzi) | 9% |

| Dioscorea (shanyao) | 9% |

| Psoralea (buguzhi) | 9% |

| Nutmeg (roudoukou) | 9% |

| Terminalia (hezi) | 8% |

| Peony (baishao) | 8% |

| Saussurea (muxiang) | 8% |

| Licorice (gancao) | 6% |

The ingredients have multiple actions on the spleen and intestines. Atractylodes, nutmeg, and saussurea are fragrant herbs that help resolve turbidity; coix and peony are cooling herbs that reduce heat in the intestines; codonopsis, atractylodes, and licorice support the spleen; psoralea warms the kidney; nutmeg, terminallia, dioscorea, and lotus seed are astringents.

The dosage is 2 teaspoons (about 6 grams) of granules each time, three times per day (or, in decoction form, about 120 grams of crude herbs made into tea and consumed in 2–3 doses per day). The patient may also take drugs (e.g., Imodium) in the initial phase of treatment to assure control over the symptoms.

SAMPLE CLINICAL TRIALSLi Fandong reported on the Chinese medical analysis and treatment of 108 middle-aged and elderly patients suffering from chronic diarrhea who did not reveal any intestinal infection upon stool culturing (6). According to the report, 42 of the cases could be classified primarily as belonging to the spleen/cold deficiency cold type, while 66 cases could be classified primarily as belonging to the kidney yang deficiency type (spleen yang deficiency was also present); the average age of the latter group was 5 years older than the former (61.3 years vs. 56.2 years). The basic treatment was a modified Fu Gui Lizhong Tang, with the following formulation:

| Aconite (fuzi) | 30 grams |

| Ginseng (renshen) | 15 grams |

| Atractylodes (baizhu) | 15 grams |

| Cinnamon bark (rougui) | 30 grams |

| Dry ginger (ganjiang) | 10 grams |

| Licorice (gancao) | 10 grams |

The dose of aconite and cinnamon bark were doubled for the kidney yang deficiency type. The herbs were decocted, administered in two divided doses per day, and patients were treated for 6 weeks. According to the reporting physician:

Most of the cured cases had their abdominal pain beginning to be reduced after one week of treatment; three weeks later, defecation frequency decreased. One patient of the kidney yang deficiency type presented a slight burning sensation in the stomach after initiating therapy, but after continuing daily use of the formula for one week, that symptom was eliminated, and no other ill effects of treatment were noted.

There were 78 patients said to be cured of their diarrhea with no relapse six months afterward and 18 patients who had reduced diarrhea symptoms, but continued to have more frequent than normal bowel movements.

In a clinical report on treatment of intermittent diarrhea associated with diabetes, Weng Jianxin recommended a basic formula that he considered useful both for regulating blood sugar and reducing diarrhea (7):

| Codonopsis (dangshen) | 15 grams |

| Dioscorea (shanyao) | 30 grams |

| Atractylodes (baizhu) | 10 grams |

| Coptis (huanglian) | 5 grams |

| Pomegranite leaf (shiliuye) | 10 grams |

| Psoralea (bughuzhi) | 10 grams |

| Nutmeg (roudoukou) | 10 grams |

| Astragalus (huangqi) | 20 grams |

| Terminalia (hezi) | 10 grams |

The formula could be modified for other health problems that coexisted with the diabetes. The treatment time was one month, using this formula as a decoction daily; 40 patients were so treated, average age of 65 and average duration of diarrhea was three months. For 70% of the patients, they were able to have just one formed stool per day, and the effects persisted for six months during follow-up after ceasing use of the decoction.

DIET THERAPYAccording to the Chinese concepts, certain foods are to be avoided, others to be sought out (8). The ones to be avoided include those with high fiber (e.g., celery); those which are greasy (e.g., pork); those that are cold (e.g., chilled drinks, ice cream); those that are slippery or mucilaginous in quality (e.g., most fish, soft fruits); those that increase dampness (e.g., alcohol); and those that contain wheat (e.g., bread, cake, etc.). Recommended foods include those items that are bland and easy to digest (e.g., rice, millet); those that are warming (e.g., things cooked with ginger or ginger tea); and those that are astringent (e.g., lotus seeds).

Eating habits can also contribute to chronic diarrhea. For example, patients with chronic diarrhea sometimes note the passage of undigested foods in the stool. This is interpreted as weakness of the digestive system, but is, in fact, most often a sign that the food has not been chewed adequately, leaving identifiable pieces of food to pass through the gastro-intestinal system. Inadequate chewing reduces the digestibility of all foods, and may result in increased peristalsis as the intestines react to the presence of large food particles and fermenting food materials that would otherwise have been digested first. Excessive eating also can contribute to chronic diarrhea. Large meals are poorly digested and the mass of food will stimulate intestinal peristalsis.

Zhao and Chen, in their article on food therapy, recommend the following porridges:

- Coix (30 grams, fried in advance) and ordinary rice (50 grams)

- Lotus seed (20 grams, fry in advance and powder) and ordinary rice (50 grams)

- Dioscorea (30 grams), citrus (6 grams), and ordinary rice (50 grams)

- Roasted ginger or dry ginger (6 grams) and ordinary rice (50 grams)

- Dioscorea (30 grams) and glutinous rice (60 grams, fried in advance).

- Guava leaves (10 leaves, chopped in small pieces) and ordinary rice (50 grams, fried to yellow color)

- Crataegus (20 grams, fried in advance), raw ginger (3 slices), brown sugar (15 grams)

- Red date (10 grams, without seeds; boil in advance) and saussurea (9 grams).

In sum, the patient should avoid or minimize use of the restricted foods, and rely instead on rice, millet, coix, lotus seeds, and other bland foods, vegetables, low-fat meats, and appropriate fruits (e.g., apples: these contain pectin; the astringent crab apples are especially recommended by Chinese dietitians; crataegus, especially for persons with fat malabsorption problems and those who are obese). It should be noted from Western research that, for those who have lost weight due to diarrhea, zinc deficiency should also be treated, as diarrhea contributes to lowered zinc levels and this also reduces the ability to taste foods, hence having an appetite-reducing action and furthering the loss of weight.

|

|

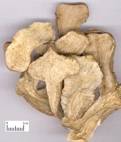

Terminalia, another commonly used herb for diarrhea; it is an astringent. Terminalia is often combined with nutmeg, dioscorea, and lotus seeds as mild astringent herbs. |

Atractylodes, one of the commonly used herbs for diarrhea; it tonifies the spleen and dries dampness. Atractylodes is often combined with ginger and either ginseng or codonopsis to aid spleen function. |

- State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology (vol. 3), 1996 New World Press, Beijing.

- Yang Shouping and Jiang Yuren, Application of Xiang Cheng San in treatment of chronic protracted diarrhea in children, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1995; 15(3): 214–219.

- Cheung CS and Belluomini J (translators/editors), Spleen, stomach, and intestines, Journal of the American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1983; 4:27–49.

- Bensky D and Barolet R, Chinese Herbal Medicine: Formulas and Strategies, 1990 rev. ed., Eastland Press, Seattle, WA.

- Zhao Lichen and Chen Fang, Food therapy for diarrhea, Journal of the American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1984; 1:22–25.

- Li Fandong, Diarrhea without pathogenic microbes in middle aged and elderly patients treated with Fuling Lizhong Tang, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine [Chinese] 1996; 37(3): 169.

- Weng Jianxin, Treatment of senile diabetic diarrhea with traditional Chinese drugs, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1999; 19(4): 264–267.

- Liu Jilin and Peck G, Chinese Dietary Therapy, 1995 Churchill Livingstone, London.

July 2010