TREATMENT OF GALLSTONES WITH

CHINESE HERBS AND ACUPUNCTURE

by Subhuti Dharmananda, Ph.D., Director, Institute for Traditional Medicine, Portland, Oregon

Cholelithiais (chole = gall; lith = stone), commonly called gallstones, is a frequent health problem and one of the major reasons for abdominal surgery, responsible for over half a million cholecystectomies (gallbladder removals) in the U.S. each year. Surgery is performed to prevent several potential problems: severe abdominal pain due to movement of a stone into the bile duct; potential blockage of bile flow causing liver and pancreatic damage; and inflammation of the gallbladder (cholecystitis), causing fever, pain, and digestive disturbance.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, a relatively new surgical technique, requires only a small incision in the navel plus two other slits made elsewhere in the abdomen to gain access to the gallbladder with microsurgical tools. This procedure results in minimal damage to surrounding tissues and quick recovery time; most patients go home within 24 hours of the procedure. About 98% of all gallbladder removals can be accomplished with this technique rather than standard abdominal surgery.

After gallbladder removal, most patients are relieved of symptoms that they have suffered, including some chronic digestive disturbances and abdominal aches that might not have been recognized initially as being related to gallstones or gallbladder inflammation. Another result of cholecystectomy is reduced bile excretion with a meal. Bile excretion, with or without a gallbladder, is an ongoing process that involves a pump-like action in the liver biliary system, dispensing fluid about six times per minute. With the gallbladder present, there is an additional pump-like action, in which bile is stored and then excreted in larger quantities during digestion of a meal. Thus, those who have their gallbladder removed can lead a normal life, but may have to be careful about eating any large quantity food at one time, particularly fatty foods, since bile is a valuable contributor to efficient digestion of fats, solubilizing the fats for enzymatic breakdown and for absorption.

Despite the improvements in surgical techniques and the generally positive outcomes, many people diagnosed with gallstones would prefer to avoid surgery and retain their gallbladder. This is to be accomplished by dissolving the stones and/or purging the stones from the gallbladder via the intestines. One alternative to surgery that was tried, but later discarded, was lithotripsy. This procedure was used for patients with large stones that involved breaking the stones into small pieces with powerful sound waves. Unfortunately, there were too many cases of bile duct blockage from the pieces of stone as they were excreted to consider this procedure generally successful. A stone dissolving therapy with bile salts, mainly ursodeoxycholic acid, is another procedure that has been tried; administered only in cases of relatively small stones. About 6-24 months of continuous use is required to attain the desired results, which is complete removal of stones. The therapy has some drawbacks, such as causing symptoms of gas, bloating, and nausea in some patients, but it is still being investigated to find improved methods that might yield superior results. A problem with these and other alternatives to surgery is that when the gallbladder has not been removed, it is common for recurrence of gallstones because the stone-forming processes are still present. Nonetheless, those who are willing to make adequate changes in diet and exercise may be able to avoid producing stones that are of a dangerous size.

Chinese medicine is commonly sought out as an alternative to surgery by those diagnosed with gallstones. It is evident from comments made by these individuals, and by Western practitioners of Chinese medicine, that many patients hope to take only a small amount of herbs in a convenient form to remove the stones. Further, they expect to do so without risk of adverse effects, such as abdominal pain due to stones becoming caught in the bile duct during expulsion; otherwise, they reject further consideration of the therapy. In order to determine whether or not such expectations are reasonable, it is necessary to examine how Chinese doctors actually treat gallstones in order to learn of the herbs to use, their dosage, duration of treatment, and incidence of adverse reactions. Acupuncture is a therapy that commonly accompanies use of herbs and is also mentioned here.

In China, the diagnosis of gallstones is a new one: it has not been part of traditional Chinese medicine prior to the introduction of modern Western medicine. Symptoms of gallstones were no doubt detected in the past, such as findings of abdominal pain and reactions to fatty foods, but the cause of such symptoms would usually be attributed to disorders such as qi stagnation and abdominal accumulation, rather than gallstones, which cannot be detected directly by traditional Chinese diagnostics.

However, since ancient times, the Chinese have been aware of the gallbladder (identified as one of the six fu organs) and aware of its ability to form stones. Gallstones of the ox (niuhuang) have long been used in traditional medicine: they were listed in the Shennong Bencao Jing (ca. 100 A.D.). It is thought that the medicinal use of the ox gallstone may have originated in India, from which it was then adopted in China (1), along with other ancient Indian remedies, such as ginger root. In the Chinese tradition, ox gallstone is used to "open the orifices of the heart," when there are symptoms of delirium, convulsions, and loss of consciousness in feverish diseases, and also to treat swellings in the throat and mouth. This latter application is addressed by the popular patent formula Niuhuang Jiedu Pian (Tablet of Ox Gallstone to Remove Toxins). In China, the extracted bile or the whole gallbladder (with bile) from several animals has been used medicinally, such as snake gallbladder given as a health tonic and as a treatment for phlegm disorders, and bear gallbladder as a treatment for injuries and back pain. The Western treatment for dissolving gallstones, ursodeoxycholic acid, is the main bile salt found in bear bile (urso = bear), though the clinical material is not obtained from bears. In modern China, bear bile (combined with curcuma and capillaris) was developed as a treatment for gallstones and gallbladder inflammation (cholecystitis).

Even with the Chinese knowledge of gallstones from animals used in medicine, early Chinese medical references to the gallbladder in humans did not include problems specifically related to stone formation. Rather, there was an understanding that the gallbladder stored and, at times, poured out bile. In a review of liver and gallbladder functions and disorders (10), this was explained:

The liver forms and secretes bile with the aid of "overflowing liver qi" that flows into and is stored by the gallbladder. The function of secretion and excretion of bile are two of the most important aspects of the liver dredging function. If there is a disturbance in the dredging function, there may be a disturbance in the secretion of bile, resulting in jaundice, bitter taste in the mouth, emesis of bile, distention and pain in the subcostal regions, abdominal distention, and decreased food intake....

Liver qi congestion and entanglement are manifestations of the liver's inability to dredge and maintain the smooth flow of liver qi. This dysfunction is defined as an imbalance of qi function and, more specifically, as qi congestion and qi stasis. The etiology may be emotional trauma, invasion of external wet-heat evil, and an insufficiency of liver blood. Liver qi congestion and entanglement is chiefly manifested as emotional depression, disturbance of qi functions, and dysfunction of the secretion of bile.

Any disturbance in the secretion or excretion of bile may alter the physiology of the spleen, stomach, and intestines, resulting in disturbance of both the qi functions and mental or emotional activities.

Put another way, the normal flow of bile is a manifestation of the smooth flow of liver qi; liver qi stagnation-often caused by emotional depression, leads to lack of bile flow. When there is a reduction of bile flow, this will disrupt the qi functions and lead to further problems, generally involving emotional distress, and thus reinforcing the pattern of stagnancy and abdominal distress. As we know now, the low level of bile flow contributes to stone formation. Since the diagnosis of gallstones, rather than simple stasis of bile flow, is a modern one, it is valuable to examine modern information of gallstones.

MODERN KNOWLEDGE OF GALLSTONES, THEIR SYMPTOMS, AND THEIR CAUSE

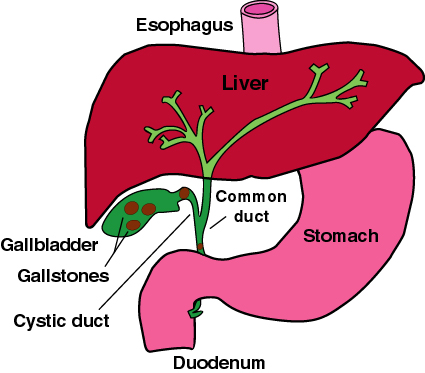

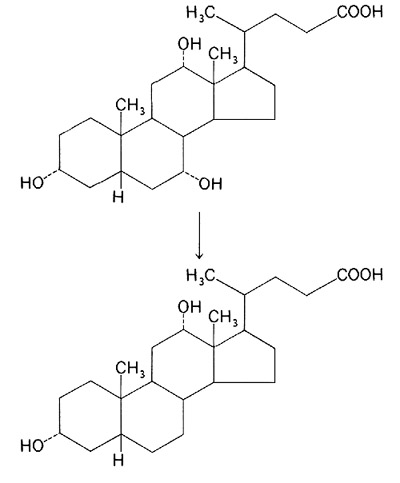

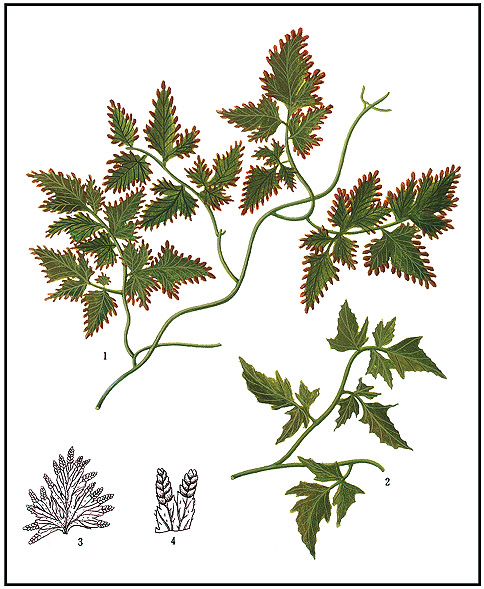

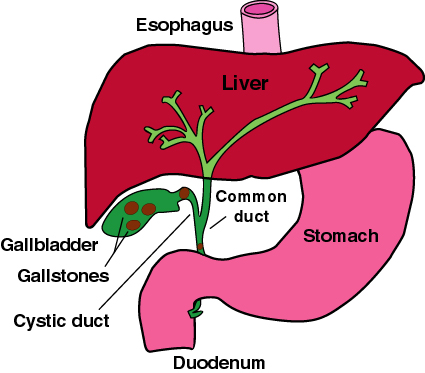

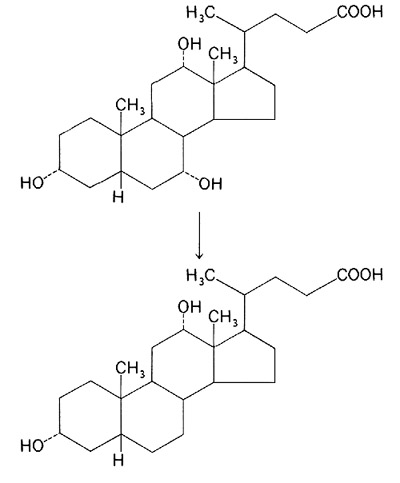

The gallbladder is a pear shaped organ that rests under the liver in the right abdomen; it is attached to the liver via the biliary ducts (see Figure 1). The gallbladder receives bile from the liver, where it is continually produced. Bile is made from cholesterol and is comprised almost entirely of a mixture of cholesterol-like fatty substances known as bile acids, mainly cholic acid and desoxycholic acid (see Figure 2). It also contains bilirubin (breakdown products of hemoglobin) and cholesterol. The bile acids combine with minerals, such as sodium and calcium to form neutral salts.

Under normal physiologic conditions, the gallbladder gradually collects bile that is being pumped out of the liver and expands to hold the bile, and then releases most of the collected bile, via the bile duct, into the duodenum (upper part of the small intestine) upon stimulus from eating. The bile combines with the partially digested food material: starches are digested during chewing, proteins upon mixing with stomach acids. In the duodenum, bile helps solubilize the fats in the food to make digestion easier, and digestive enzymes from the pancreas, including a group of lipases to break down fats, complete most of the digestive process. In cases of insufficient secretion of bile, fat metabolism can be aided by oral administration of ox bile salts, usually given in a dose of about 300 mg with each meal.

Although the exact mechanism of gallstone formation is not established, it is believed that it occurs primarily when there is a lack of sufficient bile flow-when there is stagnation of the fluids in the gallbladder. During an extended period of low bile flow, cholesterol can begin to crystallize. It is possible that defects in cholesterol processing in the liver lead to easier crystallization of the excreted material in the gallbladder. Excessive cholesterol excretion, even of normal cholesterol, can lead to easier nucleation of the crystals, since the cholesterol becomes saturated in relation to the total bile fluid.

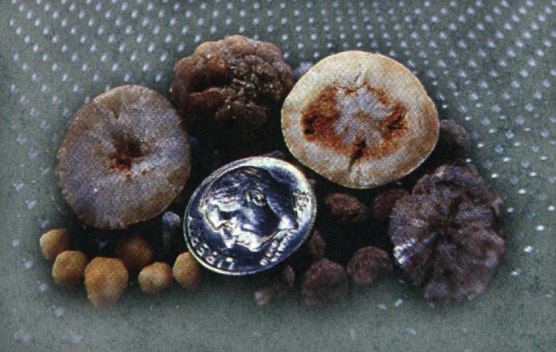

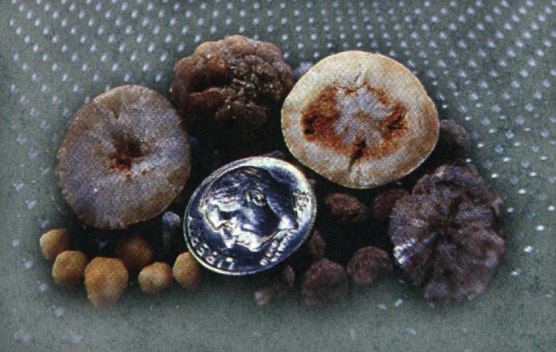

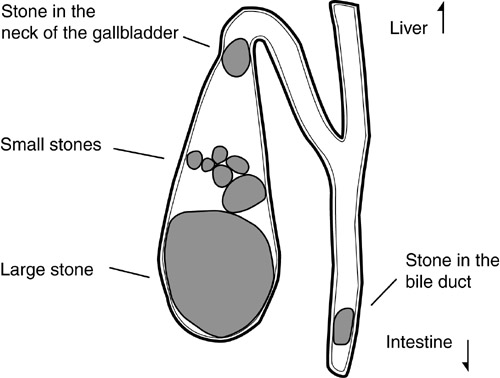

Gallstones are primarily comprised of cholesterol and calcium, as calcium bilirubinate or calcium palmitate. Depending on the precise composition, the stones may be soft (more cholesterol) or relatively hard (more calcium). There may be a large number of small sticky stones, or just one large hard stone, as well as many intermediate conditions, such as a few medium size firm stones (see Figure 3). The presence of stones may be accompanied by inflammation of the gallbladder wall (cholecystitis). Cholecystis may stimulate stones to form, or the stones may induce such inflammation, with each condition progressively worsening the other.

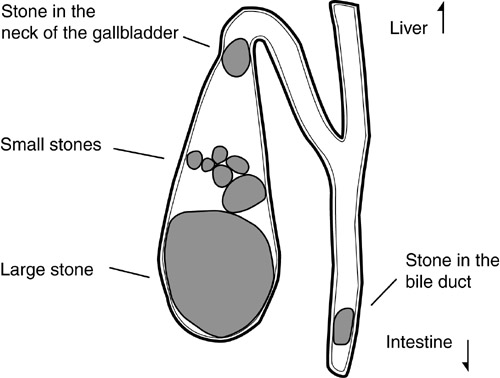

Gallstones are usually diagnosed when they produce obvious symptoms. Since only about half of persons with gallstones experience significant symptoms, many people are unaware that they have a condition that could be diagnosed. Colicky pain is one of the symptoms of gallstones that often leads to a medical visit for diagnosis; it is due to gallbladder contractions, which may last for a few minutes to several hours, with pain usually located in the gallbladder region, though it may radiate to other areas of the abdomen or to the back. A fatty meal may trigger this type of painful reaction, which can be accompanied by bloating, nausea, or vomiting. If the bile duct becomes obstructed by a stone (see Figure 4), the person can experience jaundice as the bile backs up into the liver and into the blood, while the stool becomes whitish, being deprived of the coloring bilirubin. Jaundice is often accompanied by fever and nausea. In cases of cholecystitis, a steady dull pain may be experienced instead of sharp pain. Even so, the pain may become severe at times, and usually remains localized to the upper right abdomen; additionally, there may be fever and nausea.

If the gallstones do not yield evident symptoms when they first form, the person may remain asymptomatic for many years. A relatively sudden appearance of symptoms is likely an indication that gallstones have recently formed or recently enlarged. Persons with long-term gallstone disorders are more likely to discover their disorder only if there is an ultrasound screening for other complaints. Even in the chronic asymptomatic cases, however, gallstone disorders will eventually cause symptoms in some individuals as the severity of the disease slowly progresses and causes more stagnation of the bile flow.

The major threat of untreated or unsuccessfully treated gallstones is the possibility of a gallstone blocking the bile duct. This blockage can lead to pancreatitis, which potentially develops into a life threatening condition. Also, gallstones can lead to the development of cholangitis, an infection of the bile ducts within the liver; this condition can rapidly become fatal. Since bile duct blockage is associated with strong pain, the combination of pain and threat to health are usually sufficient reason for going ahead with emergency gallbladder surgery.

Gallstones mainly occur in association with the combination of having a sedentary life style with a diet that is high in fat and low in fiber. While the process of stone formation may be slow, with stones forming over a period of years, gallstone formation can be accelerated in some circumstances. The two known situations that acutely increase the risk of gallstone formation and gallstone growth are: a substantial rapid weight loss (as occurs when obese persons follow a drastic weight control diet), and pregnancy (women who become pregnant several times are especially susceptible to stone formation). Hospital procedures, including major abdominal surgery, total parenteral nutrition (which is usually given in association with abdominal surgeries), and non-surgical gallstone treatments make a patient more likely to develop gallstones by contributing to bile stasis and/or gallbladder irritation. Finally, the use of cholesterol-lowering drugs, mainly the fibrates and the somatostatin analogue octreotide, are associated with increased incidence of gallstones. Women are more likely than men to develop gallstones, particularly after age 40. The most typical profile of a modern gallstone sufferer is a woman in her 40s or 50s who has had two or more children, is obese, and has participated in weight loss programs to attain rapid weight loss.

Practitioners of natural healing should be alerted to the fact that coffee is a stimulant to bile flow and that having patients suddenly cease coffee consumption due to the belief that coffee is harmful can increase the chances of gallstone formation and gallstone enlargement. This is particularly of concern for obese patients who adopt a dietary change that successfully reduces body weight. Additionally, recommending a diet that is too low in fat may cause further problems by reducing the bile flow.

MODERN CHINESE TREATMENTS FOR GALLSTONES

Treatments aimed specifically at removal of gallstones with Chinese herbs were first described in the Chinese literature of the post-revolutionary period. A review of accomplishments in this field was published in the English language Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, in a 1986 article: Advances in the treatment of cholelithiasis by expulsion of the gallstones (2). Beginning in the 1950's, various gallstone expulsion decoctions (referred to as lithogogues) were devised by doctors working on this problem and these were proclaimed moderately successful. The decoctions mainly contained herbs from three therapeutic categories:

- regulating qi to improve the flow of bile and vitalizing blood to alleviate abdominal aching;

- dispelling heat and dampness that are the main physiological causes of the qi stagnation; and

- removing stagnation by purgation.

The most frequently mentioned herbs in the various decoctions were: bupleurum, saussurea, chih-shih (or chih-ko), and melia for regulating qi; curcuma and corydalis for vitalizing blood; lysimachia, scute, gardenia, and capillaris for clearing damp heat; and rhubarb and mirabilitum for purgation. Sample decoctions are (9):

- lysimachia (100 grams), saussurea (15 grams), chih-shih (15 grams), scute (15 grams), melia (15 grams), rhubarb (10 grams)

- lysimachia (100 grams), saussurea (25 grams), chih-shih (25 grams), hu-chang (100 grams), rhubarb (25 grams), gardenia (20 grams), corydalis (25 grams).

According to laboratory animal studies, these decoctions relaxed Oddi's sphincter (this is mainly attributed to the action of rhubarb) and promoted duodenal peristalsis (most strongly affected by mirabilitum). It is believed that the expulsion of stones came about primarily from increasing the flow of bile (herbs with this property are called cholegogues and this action is accomplished mainly by the herbs that clear damp-heat) while relaxing the sphincter that controls the output of bile, thus allowing stones to exist. This method of therapy relies on heavy dosage decoctions with quick action, usually taken over a period of just one week.

Although most patients so treated would excrete some stones, the effectiveness of this method was somewhat limited in terms of the proportion of patients who could become either free of stones or have very few residual stones, so new methods were developed, mainly during the 1970's. The new methods involved a "general attack therapy" aimed at an even stronger and more rapid stone expulsion. The method had three steps:

- Herbs were used to stimulate the liver's production and excretion of bile to the gallbladder;

- Herbs and drugs were then given to contract Oddi's sphincter in order to get a temporary retention of bile;

- Herbs and acupuncture were administered to relax the sphincter and drain the bile.

The whole procedure lasts about 2 hours. The phase of retention of bile is carried out as long as the patient can tolerate it, which is usually about 40 minutes. The explanation of how this method works is that "with the bile rushing out in large quantities and the pressure in the bile ducts falling suddenly, stones in the latter are expelled in one fell swoop or in quick succession." This approach is carried out in the hospital and, with all diagnostics and any repeat treatments, takes only a few days, though patients may be hospitalized for longer in order to check for residual stone problems.

It is claimed that this general attacking method of therapy gives a higher rate of success than the simple stone-expelling decoctions tried previously. The strong therapy, using heavy doses of mirabilitum (magnesium sulfate) and injection of herb extracts or drugs intramuscularly, is not something that could be used in the West. Indeed, in order to tolerate the retention of bile phase and the potentially painful expulsion of larger stones, continuous anesthesia was applied via an epidural catheter in some cases. As detailed accounting of one of the regimens was outlined in Pharmacology and Applications of Chinese Materia Medica (9):

8:30 Lithogogue decoction, 200 ml orally, is given. This stimulates bile secretion.

9:30 Morphine, 5 mg, is injected. This restricts Oddi's sphincter, builds up bile pressure, and relieves pain.

10:10 Amyl nitrite, 1 ampoule, is inhaled. This relaxes Oddi's sphincter to allow bile to flow out.

10:15 33% magnesium sulfate, 40 ml, is given orally. This induces rapid bile flow and duodenal emptying.

10:20 0.5% dilute HCl, 30 ml, is given orally. This further stimulates flow of bile.

10:25 Rich meal (2-3 fried eggs). This stimulates further dispensing of bile.

10:30 electroacupuncture for 30 minutes. This causes the gallbladder to contract and alleviates symptoms of stone passage.

A similar method was reported in the Xinjiang Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (11). Patients with cholecystitis or cholelithiasis were hospitalized for an average of 34 days. They were treated daily with a lithogogue decoction containing bupleurum, capillaris, lysimachia, clematis, gardenia, curcuma, crataegus, chih-shih, and rhubarb. The general attacking method was then administered for four consecutive days using the procedure outlined above, except with a higher doses of magnesium sulfate (50 ml of 50% solution), and an additional injection of atropine. After waiting 3-5 days, the four-day course of therapy might be repeated if residual stones were detected. For chronic cholecystitis, a longer course of 10 days was utilized.

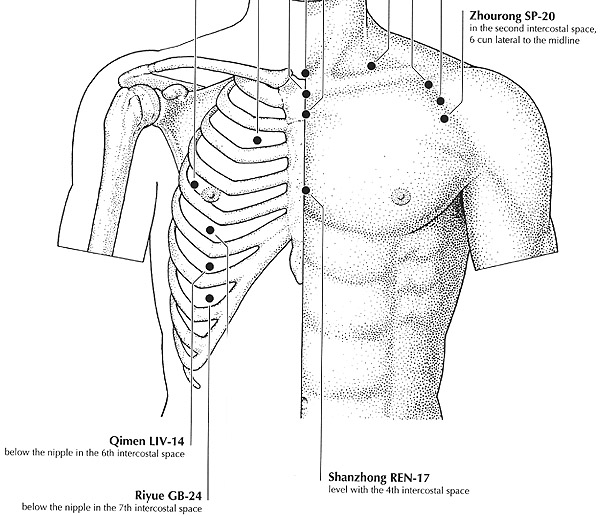

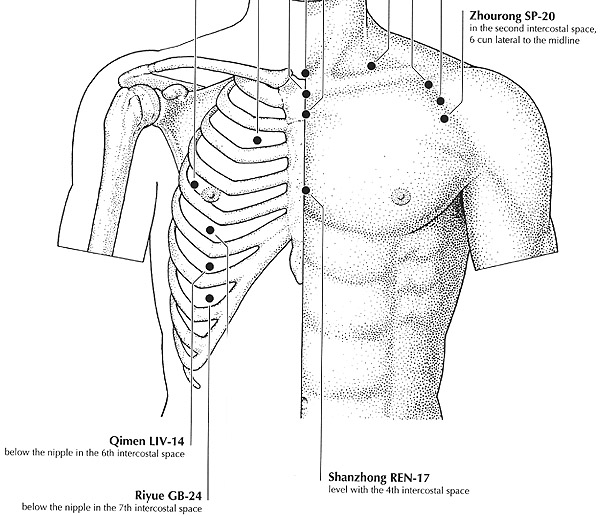

Another example of the general attacking method involves using mirabilitum along with electroacupuncture stimulus at riyue (GB-24) and qimen (LV-14; see Figure 5). The same treatment was recently tested again and claimed to be effective in expelling gallstones (3). The patients first took 30-40 ml (about one fluid ounce) of 33% solution of magnesium sulfate, and then strong electrostimulation was given to the acupuncture points on the right side only (that is, on the side where the gallbladder is located) for 30 minutes, followed by decreased stimulus for 15-20 minutes, and strong stimulation again for 10 minutes. This procedure was performed three days consecutively, once per day, to produce a full course of treatment that would expel stones.

Using such vigorous stone-expelling methods, it was reported that stones somewhat over 1 cm in diameter could be excreted. The largest stones expelled are long but not too wide, with a maximum length of about 3 cm, but a width of no more than about 1 cm. When expelling large stones, it is common for the patients to experience what is called a "stone expulsion reaction," with biliary colic, and temporary fever and jaundice (the result of stones becoming temporarily caught in the duct). Rates of such reactions are as high as 90%. Silt-like stones, which are easy to pass because of their small size, are reportedly not excreted well because they tend to adhere to the wall of the gallbladder.

In the West, one of the greatest fears associated with applying a stone-expelling therapy is the problem of billiary colic as the stone becomes stuck in the bile duct, especially at the sphincter. The pain can be extreme and may require an emergency visit to the hospital, with the usual recommendation at the hospital of immediate surgery to remove the gallbladder. By contrast, in China, the herbal procedure may be carried out at the hospital and measures are taken to alleviate the pain while continuing with the procedure. Based on the Chinese reports of the stone-expelling reactions, it appears that the rapid method of stone removal will not be acceptable in other countries.

According to the information from this review of the medical literature through 1985, the largest stones that appear capable of being passed are on the order of one centimeter in diameter. This size is probably a reasonable upper limit for anyone considering a non-surgical procedure and may represent the maximum dilation of the duct. The gentler stone-expelling methods to be used by Western practitioners who are not working in a hospital setting may not be able to expel stones of quite this size, since the strong build up of bile pressure and the sudden relaxation of the sphincter are unlikely to be accomplished. Therefore, somewhat smaller than 1 cm stones may be the largest one can expel and patients seeking to expel larger stones should be cautioned about the lower chance of success.

STONE SHRINKING WITH CHINESE HERBS

One way to pass stones more easily is to first shrink them. The ability to reduce the size of stones using herbs or other methods is not an established fact. However, certain Chinese herbs have been selected as stone-dissolving herbs. There is one traditional-style formula that is reputed to dissolve stones, called San Jin Tang, or the Decoction of Three Golds. The three golds (jin = gold) are jinqiancao, haijinsha, and jineijin. The formula was devised at the Shuguang Hospital of the Shanghai College of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Jinqiancao (literally, golden coin weed) refers to a group of herbs that are used interchangeably, and are identified by the region of China in which the herb is found:

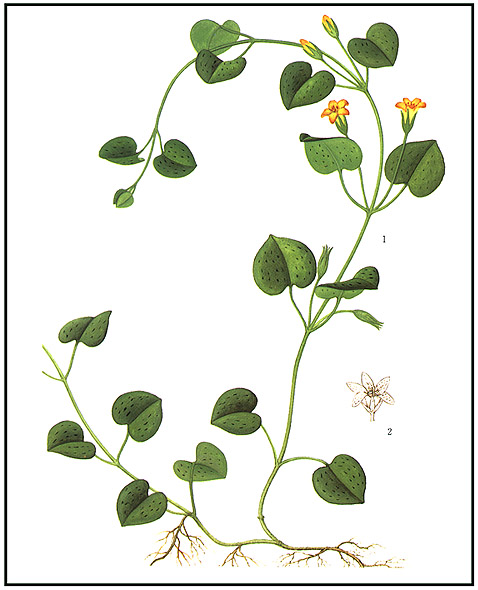

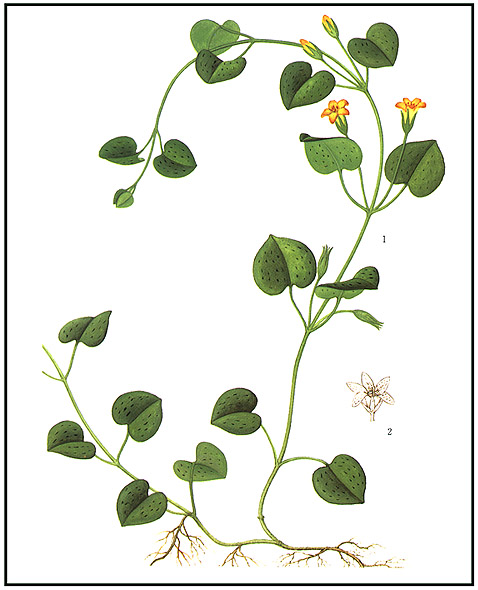

Sichuan Da Jinqiancao also called guoluhuang, is from Lysimachia christinae (see Figure 6);

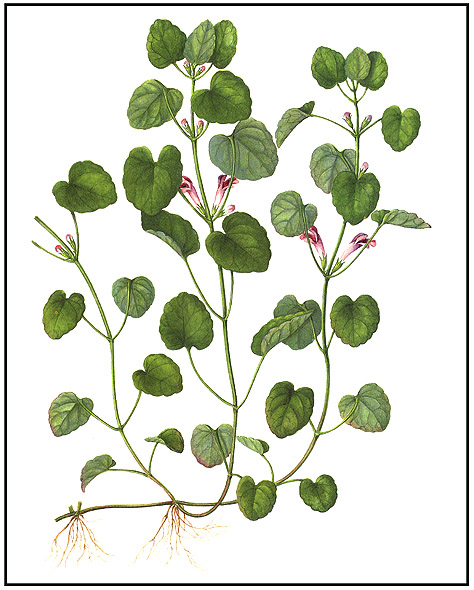

Sichuan Xiao Jinqiancao is from Dichondra repens;

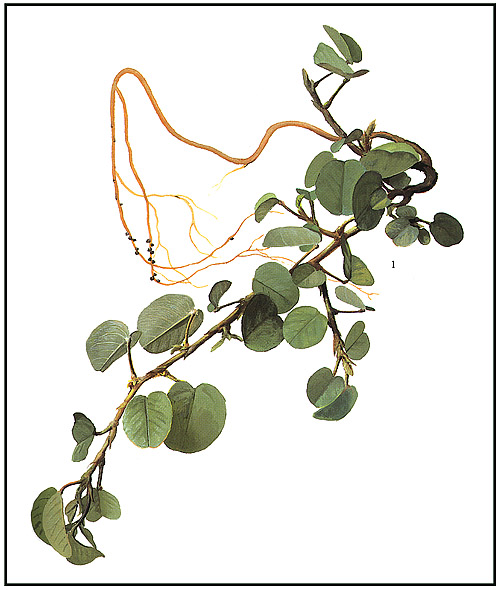

Guang Jinqiancao is from Desmodium styracifolium (see Figure 7);

Jiangxi Jinqiancao is from Hydrocotyle spithorpioides;

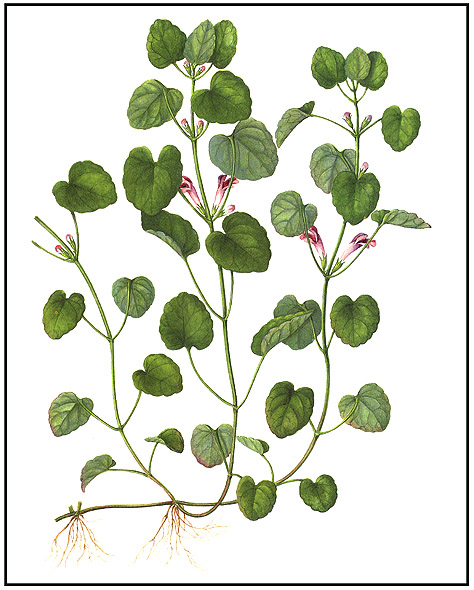

Jiangsu Jinqiancao is from Glechoma hederaea (see Figure 8); and

Kunming Jinqiancao is from Lysimachia kunmingcensis.

The first two are from Sichuan Province, one being large leaved (da) and the other being small leaved (xiao). The next is from the "guang" region of China, which includes Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hunan (formerly, Huguang); the next three are from Jiangxi Province (north of Guangdong), Jiangsu Province (on China's central east coast), and from the area of Kunming, the capital of Yunnan Province (in southwest China), respectively.

In general, these herbs are said to be sweet, cooling, and able to promote urination. They are mainly used to treat damp-heat syndromes that involve urinary retention, and they are reputed to dispel urinary stones. The herbs are mild in nature and often used in high dosage (e.g., 15-60 grams of the dried herb per day in decoction, and double that dose for the fresh herb, with some recommendations of up to 250 grams fresh herb per day). San Jin Tang was originally made with Guang Jinqiancao (Desmodium). The species of jinqiancao obtained in the West will depend on the market source relied on by the herb supplier. Among the most commonly supplied items in the West are Desmodium and Glechoma; However, the widely-used common name for the herb is lysimachia and the most frequently referenced material in Chinese texts, as well as the species listed in the Pharmacopoeia of the PRC, is Lysimachia christinae.

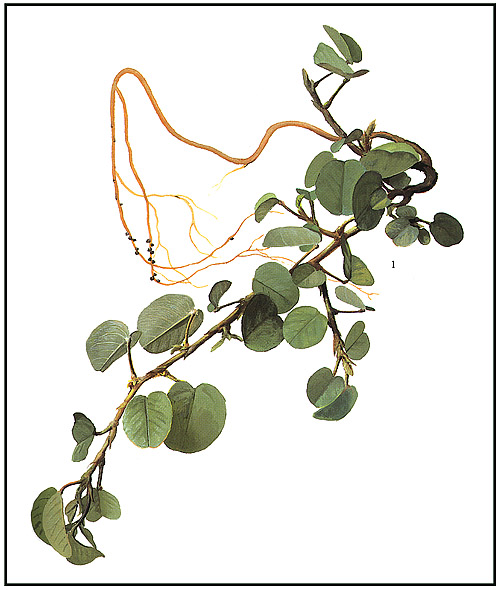

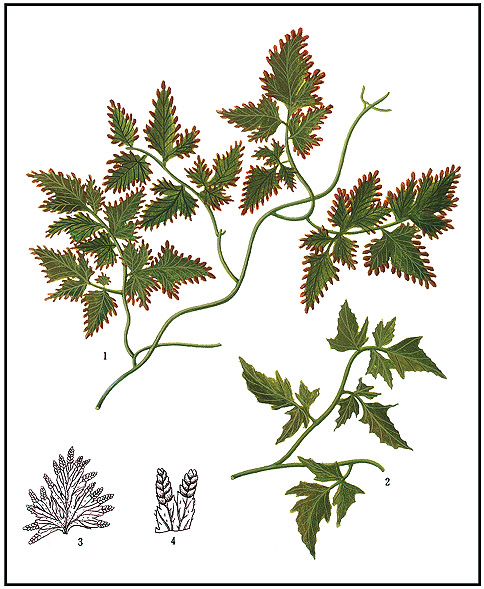

Haijinsha is a very slippery material, that looks like yellowish sea sand (hai = sea, jin = gold, sha = sand); it is the spores of a fern, Lygodium japonicum, commonly called lygodium (see Figure 9). The slippery quality is associated with the ability to dissolve stones. The material is described as sweet and cold in nature, and it is diuretic. Like jinqiancao, this herb is mainly used for damp-heat syndromes with urinary retention and it is said to help remove urinary stones. The usual daily dosage is 6-12 grams in decoction, or 2-3 grams in powder form.

Jineijin is the inner lining of the gizzard of the chicken (ji = chicken; nei = inside), commonly called gallus (the genus name of the chicken). The chicken gizzard is capable of reducing hard food masses to small pieces; it is included in some herb formulas because it is thought to resolve masses. The material has a sweet taste, a neutral property, and is used mainly to eliminate food stagnation. The usual dosage is 6-12 grams and it may be used in decoction or a smaller amount, 1.5 to 3 grams, taken as a powder.

The entire Three Golds Formula includes three additional herbs for damp-heat that affects the kidney and bladder, thus making it a treatment for urinary stones in persons with damp-heat syndrome and urinary retention. The three herbs are pyrrosia (shiwei), abutilon (dongkuizi), and dianthus (qumai) and this combination is derived from Shiwei San, a traditional formula for blocked urinary flow that contains those three herbs plus plantago and talc. A variant of the Three Golds Formula retains the talc and plantago seed of Shiwei San but replaces dianthus with achyranthes (or cyathula), vaccaria, magnolia bark, and chih-shih. The three golds may be added to any traditional formula for urinary blockage when stones are diagnosed. A typical recommendation is to add 30 grams lysimachia, 9 grams of lygodium, and 9 grams of gallus (15).

The original urinary stone formula can be adjusted to treat gallstones by replacing the three herbs for damp-heat of the kidney/bladder with herbs for damp-heat of the liver/gallbladder. The herbs suitable for this purpose generally have a bitter taste, a cold property, and a dispersing or purging action; for example, one can administer bupleurum, scute, capillaris, and rhubarb. One can also add to the therapy herbs to disperse liver-qi stagnation and accumulation, such as saussurea, magnolia bark, chih-shih, and areca peel.

Urinary stones are generally comprised of uric acid, calcium oxalate, and calcium phosphate and their formation may be related to processes similar to those involved in forming gallstones, namely low fluid flow through the renal tubules. Low water consumption, with corresponding low urinary excretion, is a major risk factor for kidney stones (high levels of dietary oxalate and high levels of acidic components in foods and beverages can also contribute to urinary stone formation). It is reasonable to question whether herb components that help to dissolve and pass urinary stones would also effectively dissolve and pass gallstones, given the differences in stone composition. Jinqiancao, one of the three golds, has been incorporated into numerous modern Chinese therapies for both liver and gallbladder diseases, including most formulas for treating gallstones and cholecystitis. In the Advanced Textbook of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology (8), lysimachia is said to be useful for stone expulsion, including gallstones: "For its effects in expelling stones, this drug is frequently used to treat hepatic, cholecystic, and urinary stones. To achieve the desired results, it is usually used in large dosage and administered for a long time." The same text mentions that jineijin "removes stones and is indicated for urinary calculus and biliary calculus." On the other hand, haijinsha is only mentioned in that text as a treatment for urinary stones. Whether or not jinqiancao actually dissolves stones, it is known to stimulate bile secretion; further, haijinsha has been used clinically in some formulas for treating gallstones (9) and was mentioned as one of the more commonly used herbs for that purpose in a recent review article examining 40 different gallstone formulas (12).

There are two main uses for a stone-dissolving formula: one is to attempt to shrink stones prior to expelling them, by reducing the outer layer that has recently been deposited and is most susceptible to re-suspension into the bile fluid, and the other is to prevent stones from forming or enlarging in persons who have a history of developing stones. The stone dissolving therapies are given for at least 2-3 months.

STONE EXPULSION WITH CHINESE HERBS

The herbs used in the strong stone expelling decoctions, as described earlier, have been formulated into easy to use tableted patent formulas that are given at much lower dosage. For example, Lidan Pian (Gallbladder Normalizing Tablets) and Lidan Paishi Pian (pai = expel; shi = stones) are readily available patent remedies recommended for cholecystitis and cholelithiasis. These tablets have a milder action than the corresponding decoctions and may be used in a complete program of gallstone therapy for treating smaller sized stones or mild gallbladder inflammation.

Lidan Pian contains lysimachia, scute, saussurea, capillaris, bupleurum, isatis leaf, lonicera, and rhubarb. Isatis leaf and lonicera are included as anti-infection herbs for cholecystitis.

Lidan Paishi Pian contains lysimachia, saussurea, capillaris, rhubarb, areca peel, magnolia bark, chih-shih, curcuma, and mirabilitum. The amount of mirabilitum present is relatively small and does not cause a strong purgative effect.

The latter formula is based on the traditional Da Chengqi Tang (Major Rhubarb Combination) of the Shanghan Lun, comprised of rhubarb, mirabilitum, magnolia bark, and chih-shih, which had been formulated as a purgative therapy for severe abdominal stagnation. This formula's action has been extensively investigated (see Appendix 1). The modification to make Lidan Paishi addresses stagnation of qi and blood in the abdomen. A decoction of the Lidan Paishi formula was tested in patients who were monitored for gallbladder function (4). The treatment, using 10 grams of each ingredient, increased the frequency of bile excretion and did so to an extent greater than that accomplished by Da Chengqi Tang, indicating a valuable contribution for the added herbs. Lidan Paishi Tablets are produced by several Chinese companies. One company lists the following ingredients, with proportions used in manufacturing: lysimachia (250 grams), capillaris (250 grams), scute (75 grams), saussurea (75 grams), curcuma (75 grams), and rhubarb (125 grams); this formula listing leaves out areca peel, magnolia bark, chih-shih, and mirabilitum.

Treatment time with stone expelling formulas is usually several months, though excretion of gallstones may begin to occur within days. In one clinical report (14), a formula called Dandao Paishi Tang (dan = bile or gallbladder; dao = movement) was administered twice daily. The formula included lysimachia, chih-ko, saussurea, scute, lonicera, gardenia, peony, red peony, atractylodes, gallus, rhubarb, and glauber's salt (xuangmingfen; sodium sulfate); in addition, mirabilitum was given separately, 40 ml each time, twice daily, at 33% solution. Treatment time ranged from one month to 10 months (a few cases continued for longer).

A formula called Paishi Tang (Stone Expulsion Decoction) was reported to be moderately effective for treating residual stones in the biliary tract after gallbladder surgery (13). The decoction contains lysimachia, capillaris, bupleurum, cyperus, melia, chih-ko, saussurea, citrus, and rhubarb (mirabilitum was given separately, 30-40 ml of 50% solution, once or twice daily). Complete removal of stones was claimed for just over half of the patients treated.

PROPOSAL FOR COMPREHENSIVE GALLSTONE THERAPY

A patient presenting with gallstone reduction or elimination as the objective of treatment should be provided with a substantial number of therapeutic approaches to be used in combination. These include:

- A diet and exercise program that emphasizes a low fat, high fiber diet and regular daily exercise. For obese patients, a carefully monitored diet with appropriate caloric controls should have a goal of gradual weight loss of not more than 2 pounds per week on average. A digestive enzyme preparation that includes ox bile and lipase may be used to help treat symptoms of poor fat digestion.

- A regular meal schedule that encourages the gallbladder to fill completely between meals. This means minimizing snacking (which is an approach contrary to some dietary recommendations for managing eating disorders and some other health problems).

- Daily consumption of stone dissolving substances, including the "three golds" and, if possible, bile salts.

- Consumption of moderate amounts of coffee (with or without caffeine) and/or other herbs that promote bile flow (mainly herbs that treat qi stagnation and damp-heat).

- Acupuncture therapy to regulate circulation of qi, purge the gallbladder, and alleviate pain in the gallbladder region (see Appendix 2).

- A gallstone purging therapy to eliminate stones that have a diameter of less than 1 cm, to be taken over a period of several days. This therapy would include rhubarb and mirabilitum.

The dietary program is no different than that widely recommended for maintaining health and normal body weight, such as following the U.S.D.A. food pyramid recommendations or the modified food pyramid for a high flavonoid diet (see: The role of dietary and herbal flavonoids in gastro-intestinal health). The exercise program is also no different than that generally recommended, which involves a daily minimum of 20-30 minutes of moderate exercise (e.g., fast walking), with more vigorous exercise for those who are physically capable. The dosage of stone-dissolving substances should be relatively high, corresponding to about 50-60 grams per day in decoction, or about 10-12 grams per day in dried extract form. As with the treatment using bile salts, stone-dissolving therapies may require as much as six months continual treatment. The gallstone flushing therapy, relying on purgative herbs, may be accompanied by a high fat meal to stimulate gallbladder emptying (some Western practitioners use the so-called "liver flush" which is actually a gallbladder purge, comprised of a large dose of olive oil moderated by lemon juice).

REFERENCES

- Hong-Yen Hsu, et al., Oriental Materia Medica: A Concise Guide, 1986 Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Long Beach, CA.

- He Ruilin, Advances in the treatment of cholelithiasis by expulsion of the gallstones, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1986.

- Lu Longzhang, 26 patients with cholelithiasis treated by acupuncture therapy, Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion 1996; (2): 8.

- Deng Xuejia, et al., Video-choangiographic study of the effect of Li Dan Pai Shi Tang on biliary dynamics in 130 cases, Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine 1985; 6(5): 338-339.

- Jiang Tingliang and Fu Hangyu, Progress of experimental studies on prescriptions designed by Zhang Zhongjing, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1996; 16(1): 55-64.

- Jiang Yongsheng and Chen Yehua, Treatment of biliary colic by water injection in the region of qimen, riyue, and juque points, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1995; 15(3): 185-188.

- Wang Tianjun and Xiao Shaoqing, Auricular acupoint pellet pressure therapy in the treatment of cholelithiasis, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1990; 10(2): 126-131.

- State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology, 1995-6 New World Press, Beijing.

- Hson-Mou Chang and Paul Pui-Hay But (eds.), Pharmacology and Applications of Chinese Materia Medica, 1986 World Scientific, Singapore.

- Cheung CS and Belluomini J (translators), The liver and gallbladder, Journal of the American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1983; (2): 30-44.

- Zhang Xiangde and Ma Zonglin, Treatment of 127 cases of chronic cholecystitis and cholecystolithiasis mainly by traditional Chinese medicine, Xinjiang Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1985; (4): 25-28.

- Pan Tianfu, A review of treatment of cholelithiasis, Journal of the Shandong College of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1994; 198(3): 203-208.

- Zhang Shiguo, Treatment of post-operational biliary tract residual cholelithiasis by integrated Chinese and Western medicine, Sichuan Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1986; 4(1): 32-33.

- Chen Ying, Treatment of 67 cases of choelithiasis by integrated Chinese and Western medicine, Chinese Traditional Patent Medicine 1989; 11(10): 24-25.

- Yan Wu and Fischer W, Practical Therapeutics of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1997 Paradigm Publications, Brookline, MA.

August 2001

APPENDIX 1: Da Chengqi Tang

In the Shanghan Lun, three formulas named Chengqi Tang were presented: Da Chengqi Tang, Xiao Chengqi Tang, and Tiaowei Chengqi Tang. All three are purgative preparations with rhubarb as the common ingredient. Tiaowei Chengqi Tang includes mirabilitum and licorice, while Xiao Chengqi Tang includes chih-shih and magnolia bark. Da Chengqi Tang includes all the ingredients except licorice. These formulas have been studied as part of a larger and ongoing evaluation of Shanghan Lun formulas (5). All the prescriptions stimulate intestinal peristalsis, with Da Chengqi Tang having the strongest action. Rhubarb acts as a secretory purgative that stimulates the large intestine; it produces a delayed laxative action and cannot soften hard stool; mirabilitum acts as an osmotic purgative, affecting mainly the small intestine. By combining mirabilitum with rhubarb, the laxative action is quicker (due to the effect of mirabilitum on the small intestine) and the moisture retaining effect of magnesium softens the stool. In Western studies of gallbladder function, mirabilitum is known as a useful agent to induce bile flow and to purge the duodenum. Magnolia bark and chih-shih act mainly on the large intestine and have a milder effect than rhubarb and mirabilitum; magnolia bark and chih-shih also serve to dispel gas and bloating.

When rhubarb and licorice are cooked together, as in Tiaowei Chengqi Tang, there is a reduced laxative effect, due to binding of licorice ingredients with anthraquinones, the main laxative component of rhubarb. But, without the mirabilitum, the laxative effect is more limited, so that Xiao Chengqi Tang has the mildest laxative action of the three Chengqi formulas.

APPENDIX 2: Acupuncture for Gallstones

It is unclear whether acupuncture, by itself, can cause expulsion of gallstones, but acupuncture is used to treat symptoms of gallstones, such as billiary colic. The two acupuncture points mentioned in this article, qimen (LV-14) and riyue (GB-24), are the main ones mentioned in the literature. These points lie over the liver on the right side, and are located one rib apart and directly below the nipple. Only the right side is treated. An extensive analysis of the value of these points was presented in an article on treatment of biliary colic (6), along with brief mention of the nearby point juque (CV-14). In the discussion of their treatment, the authors stated:

The theory of acupuncture and moxibustion of Zhang Zhongjing [author of Shanghan Lun] is an important component part of his academic thinking, of which the frequent use of qimen point is quite characteristic. The indications of qimen point include fullness of abdomen, delirium, fullness of the chest and flanks, distention of gastric region resistant to pressure, and fever or alternative spells of fever and chills, which are similar to the clinical manifestations during a bout of biliary colic....

We found that the most sensitive and tender point of qimen [among our patients with biliary colic] is in the area defined by the lines connecting qimen, riyue, and juque points, which, according to traditional Chinese medicine, is the dividing line between the liver and the gallbladder, and is indicated mainly for treating diseases of the internal organs in the vicinity. Qimen is the mu point [alarm point] of the liver, riyue is the mu point of the gallbladder, and juque is the mu point of the heart. The front mu points are used mainly in the treatment of diseases of the internal organs. Various painful lesions are the result of failure of the heart and liver to remove stagnancy of vital energy, leading to impediment to the flow of qi of the gallbladder, thus producing the pain. Basing on the principle of treating pain by needling the location where pain exists, the most marked tender spot was detected in the region of the three points....

Other points frequently mentioned in the literature for treating gallstones include the lower leg points yanglingquan (GB-34), qiuxu (GB-40), and zusanli (ST-36); in addition, there is an extra point known as the gallbladder point (dannangxue), just below GB-34 (about 1-2 cun lower). The nausea and pain associated with cholecystitis and with billiary blockage is treated at neiguan (PC-6) and zhigou (TB-6), above the wrist. In explaining the use of these points, the Advanced Textbook of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology states:

Qimen and riyue are the front mu points of the liver and gallbladder meridians respectively; zhigou and yanglingquan can relieve hypochondriac pain, while zusanli helps strengthen the spleen and disperse dampness-heat.

Ear acupuncture developed a reputation for being a method for expelling gallstones during the 1980s (7). It was reported to be especially effective for the damp-heat type and less so for the qi-stagnation types of patients, but not effective for those with qi deficiency. Over 60 auricular points have been used in the treatment of gallstones, making it difficult to pick out points that might be particularly effective. Not surprisingly, the most commonly used points were those associated with the liver, gallbladder, bile duct, pancreas, duodenum, stomach, spleen, and small intestine. A course of treatment would be thirty days with pressure applied to the point using various kinds of pellets, especially vaccaria seeds (which have a sharp point and may be substituted by the small "ear tacks"). Pressure would be applied for 20-30 minutes after meals (about 15 minutes after eating). Despite the high efficacy of the therapy in alleviating symptoms, the number of cases reported to have complete elimination of stones was usually only about 10%, sometimes as high as 20%. During treatment, stone expulsion would yield a sensation of distention or pain in the region of the gallbladder.

Unfortunately, it was found that in patients who had only a portion of the stones expelled, new stones appeared very rapidly, sometimes leading to a worsened condition after treatment. One researcher, Shang Cenruo of the Nanjing College of TCM, cautioned that a higher efficacy of ear acupuncture for stone expulsion should be attained before recommending wide spread use of the technique. Other researchers noted superior effects when ear acupuncture was combined with herbal therapy. In an extensive review of the experiences and opinions expressed by several researchers in this field (8), the editor concluded that:

In some reports, the therapeutic efficacy was overestimated or overstated. As far as I know, besides exaggeration, the most important reason for this was that evaluation was not made on a scientific basis....Obviously, it is not sufficient to evaluate the therapeutic effects merely on the basis of presence or absence of subjective symptoms and the amount of gallstones expelled with the stools. At present, auriculo-point seed pressing therapy may be used to expel gallstones, but the evacuation rate is still very low. This remains to be further improved.

The therapeutic efficacy [among the results reported by several researchers] was basically the same with different prescriptions of otopoints: part of the gallstones could eventually be expelled from every patient. Local inflammation and clinical symptoms were accordingly alleviated or disappeared with a decrease in the amount of gallstones in the biliary tract. In some patients, the duration of colicky attacks became shorter, and the time interval between two attacks became longer. This is the main reason why this therapy has won the patient's confidence....

I propose that in order to further enhance the therapeutic efficacy of this therapy, the following measures be adopted:

- Some research centers or cooperation groups headed by a department concerned [with this special topic] should be established;

- Clinical practice must be combined with experimental research so that the mechanisms of evacuation of gallstones can be clarified, and the most effective methods and otopoints be detected through the latter which, in turn, guide clinical practice; and,

- Since it is quite difficult to enhance the therapeutic effects by merely using the auriculo-point seed pressing method for treating cholelithiasis, it can only be taken as the main method in a combined therapy.

Figure 1: The gallbladder and biliary ducts.

Figure 2: cholic acid and desoxycholic acid.

Figure 3: Assorted gallstones.

Figure 4: Stones depicted in the gallbladder and biliary duct.

Figure 5: The acupoints riyue (GB-24) and qimen (LV-14).

Figure 6: Lysimachia christinae.

Figure 7: Desmodium styracifolium.

Figure 8: Glechoma hederaea.

Figure 9: Lygodium japonicum.